Overview

Introduction

Mexico City, Mexico, embodies the word megalopolis. It is one of the world's most populous cities, at the same time modern and cosmopolitan yet sprawling and ramshackle. Its industry, traffic (with accompanying smog), hotels, restaurants, museums, architecture, historic sites (both Spanish and Aztec) and performing arts are everything you'd expect of a world-class city.

However, Mexico City's poverty-stricken neighborhoods are textbook illustrations of the problems encumbering developing nations. Although Mexico City does present challenges for visitors, its rewards make a visit well worth the effort, and there's a clear sense that this is a city on the upswing. Crime continues to decline, the air is cleaner each year, infrastructure improvements are accelerating, and the city's reputation as Latin America's "Tech Hub," is bringing new life and money to the capital.

Those who dive into the fray often become addicted to the city's energy, food and attractions.

Must See or Do

Sights—The Zocalo (main plaza, with its surrounding Historic Center); the magnificent pyramids of Teotihuacan, a short ride from the city; Ballet Folklorico de Mexico, a spectacular presentation of Mexican music and dance.

Museums—The outstanding Museo Nacional de Antropologia in Chapultepec Park; Museo Dolores Olmedo Patino, containing works by Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Museo Frida Kahlo, located in the famous blue house in which Kahlo grew up and later lived with Diego Rivera; Museo de Franz Mayer, housed in a restored 16th-century hospital; the Museo de Arte Popular, which has the best collection of folk art in the country.

Memorable Meals—High Mexican cuisine at Pujol or Dulce Patria; Spanish fusion at Biko; regional folk music and huachinango a la Veracruzana (red snapper, Veracruz-style) at Fonda del Recuerdo; Oaxacan-influenced cuisine and a hip setting at Los Danzantes; churros and hot chocolate at Churreria el Moro; tacos pastor at El Tizoncito; seafood at Contramar; Italian in a gorgeous mansion at Rosetta; breakfast in the historic center at La Casa de los Azulejos.

Late Night—Hot salsa nights at Mama Rumba Cuban bar; the mind-altering mescal of La Botica; margaritas and a piece of history at La Opera Bar downtown; pricey cocktails that help pay for the sensuous nighttime vistas from the rooftop bar La Terraza at Condesa D.F.

Walks—Bosque de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Park), a delightful place to walk, although no one should try to cover all of its 2,100 acres/850 hectares at one time; the pedestrian-friendly, park-dotted neighborhoods of Roma and Condesa; Centro to Alameda Park.

Especially for Kids—The Zoologico de Chapultepec (the zoo); kid friendly art displays at the Museum of Popular Art; rollercoasters at Six Flags Mexico City; the Papalote Museo del Nino (the Children's Museum); Mexico's largest aquarium, Acuario Inbursa.

Geography

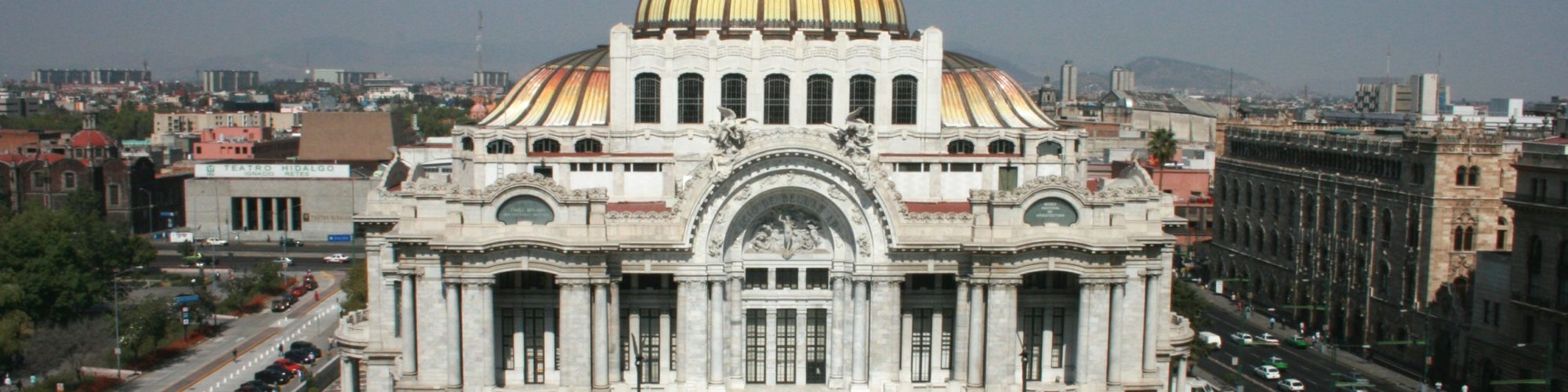

Mexico City lies in Mexico's central valley, roughly in the middle of the country. The heart of the city is the Zocalo, a large plaza flanked by the Cathedral and the National Palace. Surrounding it is the Centro Historico (Historic Center), which is where you'll find the heaviest concentration of sights, including the Aztec Templo Mayor and an abundance of Spanish colonial buildings. The park just west of the Zocalo, Alameda Central, is lined with museums, and the Palacio de Bellas Artes is at its northeastern corner. Paseo de la Reforma, the city's most famous and elegant boulevard, runs near the western edge of the Alameda Central. From there it travels southwest to Chapultepec Park, the site of several museums and the zoo.

There are many points of interest in other colonias (neighborhoods) southwest of the Historic Center. About halfway between the Historic Center and Chapultepec Park is the Zona Rosa, a once-flourishing commercial neighborhood of restaurants, shops and nightspots, though it's looking more down-market these days. Just south of Zona Rosa is Condesa, a nice residential area that also has its share of trendy restaurants and bars, which bleed into Roma, the next area to take the hip and trendy baton.

North of Chapultepec Park is Polanco, a posh neighborhood with many fine hotels, restaurants and luxury shops. The northern part of the city is newer, sleeker and still growing, with high-profile architecture and burgeoning museums and attractions. About 6 mi/9 km south of the city center are Coyoacan and San Angel, both with lovely colonial buildings housing museums, galleries, cafes and shops. There are many other colonias in the city, and knowing them by name is often essential in finding your way to an address. You'll often see them noted with the abbreviation Col., as in Col. Roma.

Its size and complexity make Mexico City difficult to navigate, at least for the newcomer. If you want to explore it in its entirety, consider buying a comprehensive map such as the Guia Roji, available in bookstores and newspaper stands in the city center, and consider navigating the colonias by foot—Mexico City is a wonderful walking city. Naturally, a smart phone map can make navigation easier: get one that works offline or buy a local data SIM card for an unlocked phone.

History

Mexico City's history holds more than 600 years of destruction and rebirth. It began as Tenochtitlan, the clean, well-ordered capital of the Aztec empire. In 1521, it was razed by Hernan Cortes and his conquistadors to make room for a European-style colonial capital, with an enormous central plaza and a neo-Gothic cathedral. For the next 300 years, the Spanish rulers prospered while the Aztecs and mestizos lived in poverty, marginalized by the ruling elite.

In 1810, resentment toward the Spanish exploded into war. After 11 years of fighting, Mexico won independence from Spain, then plunged into almost a century of political violence. During this period, the city was invaded first by the U.S. and then the French, who left behind an Austrian archduke as emperor Maximilian II. Maximilian and his wife, Carlota, refurbished and lived in the castle of Chapultepec, and Maximilian laid out the grand Paseo de la Reforma before he was executed in 1867 by forces loyal to reforming President Benito Juarez.

The unrest came to an end only after strongman Porfirio Diaz took the presidency in 1877. The 33-year presidency—many say dictatorship—of Diaz was a period of unprecedented peace and prosperity for the city, much of which was rebuilt. But Diaz's rule was oppressive; he banned political opposition, democratic elections and a free press, and the city's prosperity was enjoyed by an elite minority.

The Mexican Revolution of 1910-20 finished all that. During the fighting, parts of the city center were leveled, and residents lived in constant fear. When it ended, Alvaro Obregon, a revolutionary leader from Sonora, became president for a four-year term of national reconstruction. His successor, Plutarco Elias Calles, angered Catholics by closing churches and convents and passing laws against religious displays in public. This led to more violence, known as the Cristero Rebellion, which lasted until 1929.

At that time, Calles organized the National Revolutionary Party (PNR), a precursor to the Institutional Revolution Party (PRI), which ruled the country—with sometimes despotic methods—for the seven remaining decades of the 20th century. (Mexicans still recall 2 October 1968, when perhaps as many as 400 protesting students were massacred by police near the main plaza.) Prosperity returned for a time, thanks in part to the discovery of large oil deposits in the country's south. Development focused on the capital, and the poorer suburbs swelled with migrants from the countryside who sought work in the new factories.

Growth could not be sustained, however, and a series of currency devaluations plus a flight of capital to foreign real estate and banking institutions spread a pall of neglect over the once-elegant city center. In 1985, an earthquake killed more than 10,000 people and leveled dozens of buildings. In the wake of the tragedy, Mexico implemented stricter building regulations, and these laws have become the foundation for a safer, sleeker skyline.

In 2016, Mexico City dropped its federal designation and held its first mayoral elections. The political plurality has revitalized the city, and political activism flourishes. As a result, Mexican voters broke the PRI's seven-decade lock on the presidency when they elected Vicente Fox of the National Action Party (PAN). The PAN triumphed again when Felipe Calderon narrowly defeated former Mexico City Mayor Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador of the Democratic Revolution Party (PRD). In protest of the election result, Lopez Obrador and his followers camped out in the central Zocalo plaza and along the Paseo de la Reforma for months, snarling traffic and angering some residents. He even tried to set up a parallel presidency, which failed. Mexico's political pendulum continues to swing and in 2018, following Enrique Pena Nieto's one-term stint, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador was elected as Mexico's president.

For good reason, Mexico City has earned the nickname Silicon South, and the tech boom has fueled construction in Mexico City proceeds at a breakneck pace, and in the historic center, efforts are ongoing to refurbish the colonial buildings, clean up parks, improve lighting and safety, wash off centuries of grime and attract new investment. It is working: The center is getting livelier all the time and the change in appearance from a decade ago is dramatic. Hip boutiques and hotels are opening in the center, while skyscrapers battle to be the tallest along Paseo de la Reforma.

The city, meanwhile, has been spreading westward—upscale residential neighborhoods, hotels, company headquarters, shopping malls and major banks have opened in Sante Fe, once the site of the biggest city dump with accompanying poverty. It now looks much like an office park area of San Jose, California, much to the joy of those who zip in and out by car.

Potpourri

On 29 January 2016, President Enrique Pena Nieto removed Mexico City's status as a Federal District, though many locals still refer to the city as "D.F." With its new status, the capital now boasts 16 boroughs, each with its own mayor and city council members. The city's logo, CDMX, stands for Ciudad de Mexico.

The word zocalo, commonly used to refer to Mexico City's central plaza, Plaza de la Constitucion, literally refers to the base or pedestal of a statue or sculpture. Legend has it that in 1843, then-president Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna ordered the architect Lorenzo de la Hidalga to build a monument in the plaza to honor the heroes of Mexican independence. But because of the political instability of the time, the architect had to cease construction after building only the base to the monument. Locals have referred to the plaza as the Zocalo ever since.

When it comes to pilgrims, only the Vatican boasts more visitors than the Basilica de Santa Maria de Guadalupe.

The pedestrian alleyway that borders the Casa de Azulejos (House of Tiles), near the Palacio de Bellas Artes, is known as the Callejon de la Condesa (Alley of the Countess). It is said that the alley was once reserved for the royal carriages. Yet another legend has it that once, many years ago, two noblemen entered the alley in their respective coaches, from opposing ends. Upon meeting in the center and realizing there wasn't enough room to pass, each insisted the other retreat to the opposite end of the alley—and each refused, unwilling to cede any noble pride. Supposedly their impasse lasted three days, until it was ended by the viceroy himself, who ordered them both to retreat from the alley simultaneously.

Founded in 1325, Mexico City is the oldest capital city of the Americas, though it was the Aztecs, not the Spaniards, that put it in the record books.

According to city authorities, some 500,000 unlicensed vendors operate on the capital's streets, representing roughly 40% of local economic activity. They sell just about anything, from pirated software to clothes to electronics. Certain areas used to be so clogged by vendors that there was practically no room for pedestrians to pass through, but regular crackdowns have moved the activity to designated park areas and wider main thoroughfares.

Only London has more officially recognized museums than Mexico City.

If traffic is hopelessly snarled and it's not rush hour, especially on Paseo de la Reforma, chances are that a protest march is under way. Protests are a part of daily life in Mexico City—don't be surprised to see people shouting and waving banners, especially near the center, and don't assume that the sight of police in riot gear means there is anything dangerous going on. The demonstrations are sometimes colorful or strange—for example, one group of farmers annually strips to their underwear in front of national monuments. Don't expect Mexican friends or contacts to have much information on what's going on—most city residents have trouble keeping track of the dozens of protests that take place during any given week.