Tale of Tales: The Magic Carpet, the Fabled Egg and the Elephant Bird, by Paul Theroux

American novelist and renowned travel writer Paul Theroux’s Tale of Tales chapter is part of a series commissioned by Silversea Cruises to chronicle a world cruise through the eyes of some of the world’s best writers, photographers and visual artists. This anthology celebrates all those who were part of the extraordinary 2019 World Cruise. Those who travelled further into the world to discover its beauty. Those who were fascinated, amazed and delighted by the stories they encountered – the stories they shared – and the story they created. Theroux traveled from Mombasa to Cape Town onboard Silver Whisper. This is his tale.

We had left Zanzibar and were sailing to Madagascar on a calm sea in perfect weather. Standing in the open air on an upper deck of Silver Whisper, I felt the ship softly rising and falling beneath me, as undulant as a magic carpet – the sort of carpet mentioned in the Arabian Nights, in the tale of “The Three Princes and the Princess Nouronnihar.” In this tale the carpet seller says to Prince Houssain, “Whoever sits on it as we do, and desires to be transported to any place, be it ever so far off, is immediately carried thither.”

This sounds fanciful and forced, typical travel writer hyperbole, gushing sentimentality about the luxury ship. But wait – this image stayed with me for days, and what came next was like the unfolding of a fable that justified the gush. I had always wanted to visit Madagascar, not only for its lemurs, a primate found nowhere else on Earth, but also to see the land and people – some from mainland Africa, others descended from ancient South East Asian voyagers. I’d been reading about the island for years.

Marco Polo mentions Madagascar in his Travels (Book 3, Chapter 33) – he’d heard of it on his way back to Venice from China around the year 1291: “Madeigascar is an island towards the south, about a thousand miles from Scotra (an island off the Yemeni coast). The people are all Saracens, adoring Mahommet. They have four Esheks, i.e. four Elders, who are said to govern the whole island. And you must know that it is a most noble and beautiful island, and one of the greatest in the world…The people live by trade and handicrafts.”

The other great early traveler Ibn-Battuta, a near contemporary of Marco Polo, who roamed the entire Muslim world from 1325 to 1353, also mentions Madagascar as a place of wonders. He had sailed from Somalia to Kilwa on the East African coast (in present day southern Tanzania), where like Marco Polo he heard of Madagascar’s wonders.

And from the magic carpet of Silver Whisper I could now see the “noble and beautiful island,” the green hills and jungly coast of northwest Madagascar. After being taken to the pier near the town of Nosy Be, I boarded a small boat with other passengers and we sailed about three miles to a cove lined with bamboo and thatched huts, and a welcome at the fishing village of Komba.

At the forested edges of Komba live mild-tempered black lemurs, so mild in fact that if you happen to be holding a piece of banana, a lemur will leap from a nearby branch to your shoulder and seize it with its long fingers – as happened to me – and for the time it takes to eat it, the lemur will stay contentedly on your shoulder.

I wandered away from the lemurs and the pink and blue chameleons clinging to tree branches, and the boa constrictor that had been placidly sunning itself on the top of a stone wall, and I made my way along the muddy path through Komba village. In stalls and at village huts, local women and men were selling embroidered tablecloths, and intricately stitched cushion covers, and wooden carvings, as well as spices and T-shirts.

“Regardez, monsieur, beau, [Look, sir, beautiful cloth]”, one woman said at the doorway of a small hut. She welcomed me with a dishtowel, the map of Madagascar picked out on it in colored thread. And as she did so my eyes became accustomed to the darkness of the hut and I saw several large symmetrical white objects, twice the size of footballs, but the same spheroidal shape, and cream colored, and very odd.

“Carvings?” I asked.

“Oeufs,” she said – eggs.

“Really?”

“Oui, d’un oiseau – un grande autruche.”

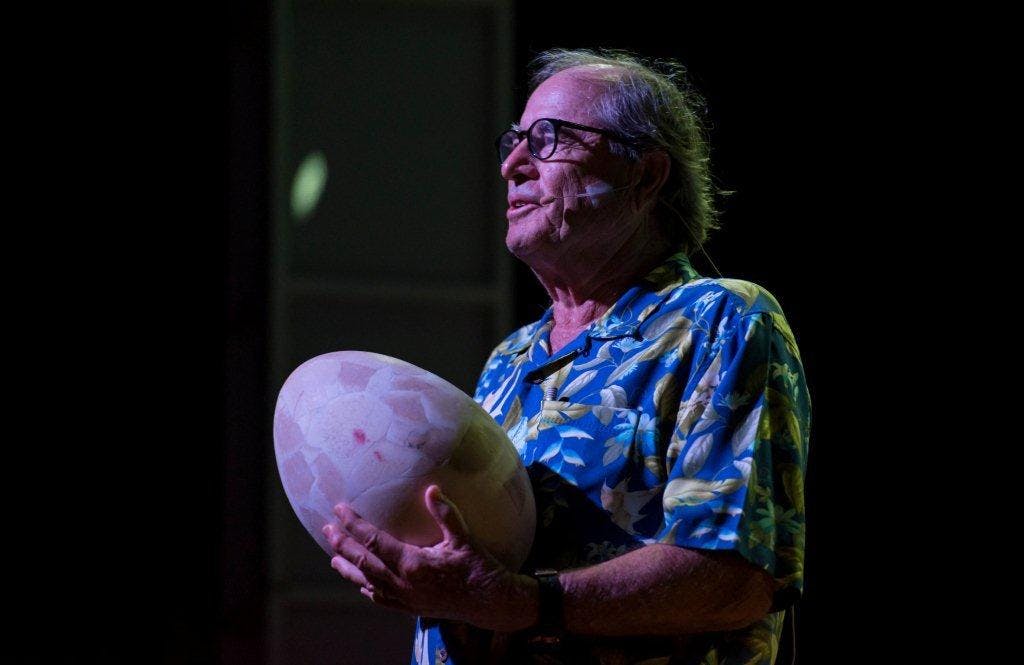

What sort of great ostrich could this be that would lay an egg this size? I hoisted one up – I needed two hands it was so heavy, but holding it in my arms I saw that it was beautiful and smooth, made of a mosaic of many smaller pieces of eggshell, the largest egg I’d ever seen.

“How much?”

“Cinquante euro.”

She was delighted, and danced, when I offered her forty. Could something this size really be a bird’s egg, and if so, what sort of bird?

In the small boat back to Silver Whisper some curious passengers asked me what I had in my bulging bag. I opened the bag and showed them my marvel – it was much too bulky to take out.

“An egg.”

One woman smiled, another laughed outright, believing that I had been foxed by a curio seller in Komba, and a third forthright woman said, “That’s not possible.”

Yes, it looked preposterous, but I said, “Okay, if it’s not an egg, what is it?” To learn the answer I needed to go back to Marco Polo, and Ibn-Battuta, and The Arabian Nights.

One of the wonders in Madagascar that Marco Polo mentions is a mythical bird, which he takes to be a “Gryphon” – or griffin– said to be half lion and half bird. But this Madagascan bird he describes is enormous. “And it is so strong that it will seize an elephant in its talons and carry him high into the air, and drop him so that he is smashed to pieces; having so killed him the bird gryphon swoops down on him and eats him at leisure. The people of those isles call the bird Ruc, and it has no other name.” Then Marco Polo becomes pedantic: “But this I can tell you for certain, that they were not half lion and half bird, as our stories do relate, but as enormous as they be they are fashioned just like an eagle.”

A few decades after Polo’s observation, the traveler Ibn-Battuta sailing from the East African coast – known as the Sea of Zanj then − sees an island rising from the ocean. But instead of rejoicing that land has been sighted the sailors on his junk begin to weep with fear. Ibn-Battuta calls out, ‘What is the matter?’

They reply, “What we took for a mountain is ‘the Rukh.’ If it sees us, it will send us to destruction.” The creature was then some ten miles from the junk. “But God Almighty was gracious unto us, and sent us a fair wind, which turned us from the direction in which the Rukh was; so we did not see him well enough to take cognizance of his real shape.”

And Ibn-Battuta describes Madagascar − “The island is in the southwest” –and the great bird, the Rukh – “birds which so mask the sun in their flight that the shade on the sun dial is shifted.”

Calling this enormous bird a Ruc, or Rukh, or Roc, resonated with me, since the Roc is the bird that Sindbad the Sailor encounters in his Second Voyage. In Andrew Lang’s retelling, Sindbad drops from a tree where he has been hiding, and sees a strange object, and says, “As I drew near it seemed to me to be a white ball of immense size and height, and when I could touch it, I found it marvelously smooth and soft. As it was impossible to climb it – for it presented no foothold – I walked round about it seeking some opening, but there was none. I counted, however, that it was at least 50 paces round. By this time the sun was near setting, but quite suddenly it fell dark, something like a huge black cloud came swiftly over me, and I saw with amazement that it was a bird of extraordinary size which was hovering near. Then I remembered that I had often heard the sailors speak of a wonderful bird called a Roc, and it occurred to me that the white object which had so puzzled me must be its egg.”

The Arabian Nights (or more properly, One Thousand and One Nights, the sequence of stories related by Scheherazade), were composed in the 9th and 10th Centuries; so obviously the name of the bird, the Roc, was known to later travelers. This “wonderful bird called a Roc” informed both Marco Polo and Ibn-Battuta when speaking of the enormous bird in Madagascar.

The Roc was said to be able to eat a camel, and as both Marco Polo and Sindbad testify, this amazing creature could pick up an elephant in its talons (and it picked up Sindbad, too). The egg that Sindbad sees was vast – 50 paces makes the Roc’s egg about 200 feet in circumference.

This sounds like something from Baron Munchausen, or perhaps a typical travel writer. It is well known that travelers exaggerate for effect, to dazzle the people back home. Both Marco Polo and Ibn-Battuta reported that they saw dragons on their travels and other improbable wonders (though the dragons might have been crocodiles). But consider that I started this little tale with a hyperbolic whopper, comparing a cruise ship to a magic carpet. Yet there is a grain of truth to that, and more than a grain of truth to the existence of the Roc, and the enormous egg.

I had the egg in my suite, resting on my sofa, more than a foot from end to end, crowding an entire cushion. I googled “Giant Egg” on my computer and immediately saw images of my egg, with the caption, “Egg of the Extinct Elephant Bird.” Of Madagascar.

And, with no further effort than that, I was able to identify my egg. Mine was identical to some specimens that were shown on the Internet – the pieced-together egg, a mosaic of many fitted eggshell fragments, made whole, as though Humpty-Dumpty had been put back together again. But an intact uncracked Elephant Bird egg had been auctioned at Sotheby’s in London a few years ago, the bird described in the catalogue as “a giant flightless bird, indigenous to the island of Madagascar,” an average specimen ten feet tall and weighing half a ton, “the largest bird ever to live on the planet.”

And since this big beaky bird, the Aepyornis maximus, was thought to have become extinct “at some point between the 13th and 17th Centuries,” it existed tramping through the forests of Madagascar, when the stories in the Arabian Nights were told, and written down, and in the years Marco Polo and Ibn-Battuta sailed through the Sea of Zanj. The bird was such a marvel to behold that its reputation was known among travelers in that hemisphere.

Less than a week later, Silver Whisper stopped in Durban. I went ashore and in a display case of the Durban Natural Science Museum saw some leg bones of the Elephant Bird – its yard-long femur looking like a huge log.

In the tradition of many travelers’ tales the magnificent bird was extolled, and given a fanciful name, and its size and its feats exaggerated, and the bird and its egg found its way into one of the world’s most enduring legends. Many who read Arabian Nights, or the myths of the past, are right to be a bit skeptical about the creatures mentioned.

I knew about the Roc, and as a child I had marveled at the deliverance of Sindbad by the Roc, in his voyage. But I had never imagined that it had actually lived on earth, and that I would arrive by a beautiful ship at the shore of a place I’d longed to see, and, like Sindbad, be astonished by this marvel of a giant egg, and be able to show it to my skeptical fellow passengers, and say, “Yes, this is a real egg, and there’s a story behind it. Listen – it’s an amazing tale.”

Paul Theroux was born in Massachusetts. After university, he lived in Africa, Singapore and the UK, before returning to the US in 1989. He has authored many acclaimed works, including The Great Railway Bazaar and Dark Star Safari. In 2015, Theroux was awarded the Founders Medal from the Royal Geographical Society. Approved by the Queen, the award is the highest award attainable for a traveler. He has also won the Whitbread Prize and the James Tait Black Award. Two of his works were nominated for the American Book Award and three of his novels have been made into films.