Seeking the Northwest Passage: How Inuit Knowledge Helped Unlock Its Riches

This article has been produced in collaboration with Silversea’s Corporate Business Partner, the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), which enriches guests’ expeditions with over 500 years of geographical travel and discovery.

By the 19th century, most of the inhabited world had been discovered. Few spots remained on the globe for pioneering exploration.

The Northwest Passage was an exception. It was not then, and nor is it now, merely a trip up the western coast of Greenland and a passage through Canada’s vast Arctic archipelago of more than 36,000 islands. It’s a route on which brave sailors sought glory in the name of exploration and often died doing so.

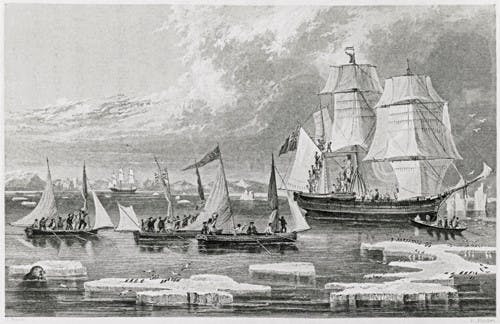

Unlike modern expeditions through the Northwest Passage, early voyages to this part of the world were often treacherous, involving a gamble on the technical prowess of the age for the ultimate adventure and a chance to make history.

The search for the fabled Northwest Passage—which would link European markets with the Orient, over the top of the Western Hemisphere—had drawn the imagination of Europeans for centuries. Starting in the mid-15th century, the Ottoman Empire levied heavy taxes on major overland trade routes between Europe and Asia. The trip around the Cape of Good Hope was very long and guarded by the Portuguese and Spanish. The search was on for the British Navy to find a new trade route to link Europe and Asia.

Back then, Canada’s Far North was a dangerous place to sail a ship: The weather was extreme, sail and steamship technologies were limited and there were huge masses of sea ice that could entomb ships for years.

Pioneering Sea Captains

Nevertheless, leading the way was a series of brilliant and tenacious sea captains—beginning with John Cabot, an Italian navigator who convinced Henry VII to fund a trip to the New World via a more northerly route than Columbus had taken. He set off in 1497, landed somewhere in Newfoundland, Cape Breton or Labrador (the precise locations remains unknown), then returned, convinced he’d found northeast Asia. The king poured more money into a second expedition, which comprised five ships and 200 men, and Cabot set off in 1498. They were never heard from again.

In the 1570s, Martin Frobisher, an English pirate, took a break from plundering French ships off the coast of Africa and made three swings toward Canada. In 1576, he sailed west, ending up at Labrador. He next reached what became Frobisher Bay before returning to England.

In 1609, the Dutch East India Company hired English explorer Henry Hudson to find the Northwest Passage. His final voyage led him to what would be called Hudson Bay, but he never made it home after sailors staged a mutiny and left Hudson, his son John and several other sailors adrift in a small boat.

For the next 200 years Great Britain did not pursue the matter, until John Barrow, Second Secretary of the Admiralty, instigated a program of Arctic exploration, sending John Ross with two naval ships, Isabella and Alexander, in search of the Northwest Passage. Aiming to solicit the help of the Inuit, John Ross left in April 1818 with numerous gifts, including sewing needles, mirrors, scissors, soap, snuff, English gin and oddities such as 40 umbrellas. His ships ended up circling Baffin Bay and it’s entirely possible they passed through villages such as Sisimiut, Ilulissat (then called Jacobshavn) and Uumannaq, which had been discovered by the Danish a century before. Across the bay in Canada, Ross named Pond Inlet after English astronomer John Pond.

Interest Revives in the 19th Century

By the 19th century, there were many more people than Danish missionaries interested in the region. In 1818, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein portrayed a mad character chasing a creature across the Arctic sea ice toward the North Pole. Other literary greats began making fantastical conjectures about Arctic themes in their novels.

Then, in 1819, William Parry, who had served under Ross, was given command of a brig and told to venture as far west into the Canadian Arctic as he could. He sailed past Baffin Island, into Lancaster Sound, past Dundas Harbour and Devon Island to reach Melville Island, which, at the 113th meridian, was the furthest west any British ship had ever gone. (Devon Island is so desolate, barren and isolated, NASA today uses it as a testing ground for Mars projects.) On his third expedition, in 1824, Parry had to abandon one of his boats, the Fury, near Somerset Island, but later received an award of £5,000 from Parliament for his efforts. One of his lieutenants, Frederick William Beechey, named one of the larger islands after his father.

In 1829, Ross made a far more successful second expedition that cut well into the archipelago to discover a sparse, tundra-covered plateau directly south of Resolute Bay called the Boothia Peninsula, as well as King William Island southwest of the peninsula. While sledging across the peninsula, his nephew James Clark Ross located the magnetic North Pole. But his ship was crushed by ice, so his sailors made a desperate 300-mile run to the wreck of the Fury, rebuilt some of the abandoned boats and rowed east until they found a whaling ship that brought them back to England in 1833.

The Expedition that Could Not Fail

In 1845, Parliament promised £20,000 for the first captain who could sail from the Atlantic to the Pacific, which led to one of the greatest naval disasters in the country’s history. Royal Navy officer Sir John Franklin’s expedition, which set off that spring, was lavishly equipped and almost certainly could not fail. His two three-masted ships had boilers to heat their cabins, tin cans in which to store food, 15-ton locomotive engines, screw propellers, iron-plated hulls and 10-inch beams buttressing the frames. (All this may sound primitive today, but it was cutting-edge back then.) There was also a library of 3,000 books, 9,450 pounds of chocolate, cigars and 200 gallons of wine.

The expedition left in May. They stopped by Disko Bay in July, headed through Baffin Bay toward Lancaster Strait, then disappeared. What followed was one of the most expansive manhunts in history, involving some 36 ships. Eventually, searchers located sailors’ graves on Beechey Island, where the expedition wintered over that first year. (The graves, which were exhumed many years later, revealed that the men died of lead poisoning from the tinned rations. They are still marked by wooden slabs on a desolate beach.) After leaving Beechey Island, it became clear that Franklin’s ships did not head due west toward the Beaufort Sea through Melville Sound, but instead turned south down Peel Strait to try to find a faster way. The shortcut was spectacularly dangerous because of the ice flows that trapped both ships in place.

Lacking the knowledge required for hunting seals or caribou, the sailors began to starve. Franklin died in June 1847. By the following April, 105 men were still clinging to life, so they struck out overland to the south, trying to reach a river on the mainland. They all died along the way; their skeletons were discovered years later.

One of the searchers was Irish explorer Robert McClure, who in 1850 set sail on H.M.S Investigator from England in search of Franklin’s lost expedition. He sailed in from the west along the Beaufort Sea coast, passing Tuktoyaktuk, then circling Banks Island until his ship got mired in ice in Mercy Bay. His starving crew, infected with scurvy, headed east across the ice by sledge and eventually hitchhiked their way back to England with other ships in the area. Technically, McClure’s expedition was the first to traverse the Northwest Passage – although partly on foot – in 1854. (In 2014 and 2016, Canadians finally found Franklin’s two missing ships, both off the coast of King William Island.)

Roald Amundsen Takes the Prize

It took another 50 years before Roald Amundsen, a Norwegian, would sail the entire Northwest Passage—from 1903-1906. Using a tiny, 46-ton herring boat called the Gjøa and a small crew, he played it smart, hugging the coasts and learning survival skills from the Inuit along the way. He spent two winters at Gjøa Haven on King William Island, then sailed past Cambridge Bay and, when he reached the Beaufort Sea, became the first man in the world to negotiate through the entire passage.

Amundsen wintered on Herschel Island, where some 1,500 people serviced the whaling industry. (The island is now deserted.) Wanting to tell the world about his exploits, he made a 700-mile overland trip to Eagle, Alaska, to the nearest telegraph station, wiring news of his success to the world on December 5, 1905. (It wasn’t until 2016 that a team of four men with sled dogs managed to retrace his route.) He then returned to his ship, which arrived in Nome on September 1, 1906. While the city has changed a great deal since his day, a bust of Amundsen commemorates his achievement outside of city hall. Amundsen admitted to the world that he would have never made the trip had it not been for the British explorers in the decades before him who put their lives on the line to discover the Arctic waterways and islands along this epic route.

On a roll? Learn more about the Northwest vs Northeast Passage.

Editor’s Note: Silversea’s own Conrad Combrink – Sr. Vice President of Expeditions, Destination, and Itinerary Management and an experienced polar explorer – brings his passion for discovery aboard Silver Endeavour’s 10-day expedition navigating the extraordinary Queen Elizabeth Islands (the northernmost islands in Canada’s Arctic Archipelago), Nunavut and Greenland’s dramatic western coast. This voyage promises rare insight and authentic experiences in one of the world’s least explored regions. The trip, beginning and ending in Pond Inlet Nunavut, is from August 10 – 20, 2023.