Insight and Awe Await on an Unusual Expedition Voyage to Australia’s Kimberley

Come sunset, the Western Australian town of Broome takes on a cheery tourist-town vibe. As the sun slips into the sea, the lawn outside Cable Beach’s Sunset Bar fills with families and couples, young and retired. A guitar player rolls into a set of folksy tunes while the cocktailers hoist the next brew. Beach prohibitions against vehicles and pets relax; utility vehicles tricked out like a scene from “Mad Max” roll onto the rocks.

A dozen camel riders clamber down from their perches, back from the day’s final saunter along the beach. Restaurants begin to fill with tourists ordering oysters and mud crabs and Aussie wines. Across the peninsula, in the main town, shops hawking locally grown pearls roll down their shutters.

Some visitors are here to soak up the winter warmth of temperatures in the 80s, an improvement from the 50s of Sydney and Perth. For others, Broome is the launch pad for flightseeing and boat tours to the remote and rugged Kimberley region of northwestern Australia.

That’s the case for 215 of us aboard Silversea’s Silver Cloud. We have just enough time for last-minute shopping in town before we leave for the 15-minute coach ride to the port. The Cloud is dwarfed by its port neighbor, an 1,800-passenger ship heading for the South Pacific. “I’m glad we’re not on that,” says a man in a seat in front of me.

During the next 10 days, we’ll sail 1,575 nautical miles along the jagged coast on our Kimberley expedition, taking in some of the planet’s most ancient geology, looking for turtles and crocodiles, and learning about the origin myths of the aboriginal people.

As an expedition enthusiast, I have a good understanding of what’s ahead. Despite brochure descriptions, some passengers seem surprised by the differences between an expedition and a classic cruise.

They learn quickly on board.

How does an expedition experience differ?

A classic cruise blends daily visits to ports advertised in advance. Shipboard, cruisers choose among a variety of musical reviews and game shows, hang by the pool and ponder their next meal. Expedition sailings deliver remote places and experiences that are otherwise difficult to access. In the Kimberley (and in the Antarctic and Arctic), nature is the star, and it determines the schedule.

All excursions involve transport by the small, tough inflatable boats called Zodiacs that take passengers along muddy banks, into rivers and up closer to wildlife and waterfalls. There are no tender boats, no handy piers, no dress-up nights and few shopping opportunities. At night, a guitarist or singer performs in one of the lounges, but the primary entertainment is what’s beyond the ship and the opportunity to learn about it.

Each evening wraps up with a briefing on the next day’s weather, tides and the plan for forays into the landscape. Every passenger is assigned a color group; groups are staggered to ensure smooth operations and rotated so everyone has a fair shot at being first – or last. After the briefing, expedition staff experts in the various “-ologies” – marine biology, anthropology and geology – give short talks offering greater detail on some aspect of the day’s experience.

On being flexible, literally and figuratively

For all aboard, flexibility is key. Tides, winds and temperatures determine each day’s schedule and sometimes alter plans. The expedition team – 26 members on this sailing – put safety first; second is an insightful nature experience. Most days involve morning and afternoon excursions – hikes, nature walks, Zodiac tours – with meals on the ship.

Age is not a limiting factor – there are plenty of fit folks on board north of 70, but agility makes for a better experience. “I wish we’d done this when we were younger,” says one woman with cranky knees. Some travelers take in the stunning scenery from the pool deck or head to the spa, rarely leaving the ship. A few classic cruisers note that there’s no musical production cabaret or organized onboard games. But most passengers are here for the forays; after dinner, they’re ready for bed.

Unexpectedly solo

I’m one of those, absorbed in the uniqueness of this place. But even for me, this cruise isn’t going quite as planned. My itinerary called for three weeks of travel with a friend, followed by a meet-up with my husband for this Kimberley voyage. When he went to board the plane, he learned from the airline staff he had no visa, although he had applied well in advance. The Australian visa website was “closed for planned maintenance.” The Australian embassy was closed for the weekend. He could not get to Western Australia before the ship’s departure. Weeks later, we discovered he was traveling with a passport we had canceled, thinking it was lost. The visa was attached to his new passport. Sigh.

I am here with 214 other passengers and learning about solo cruising.

Although most of my fellow passengers are couples, a handful of us are on our own. Most of us meet the first night at a ship-arranged cocktail reception followed by dinner with the future cruise sales manager and the entertainment hostess. On this sailing, the solos are women: an artist from South Africa whose husband is busy running a business, three retired widows and a doctor. Being on one’s own is no reason to sit home. “This is not a dress rehearsal,” says the Canadian, a fit woman who claims she will turn 80 during the voyage. (She seems far younger.)

Conversation includes the cost of a single supplement, grandchildren and books. And always, the dinner menu and which restaurants to book for future nights. Expeditions are easier for solos, some say, because you meet people on the outings. But dinner remains a challenge.

A few days later, insurance tops the agenda after a passenger is evacuated by medical helicopter. Heart attack, it’s thought. The incident reminds us that in remote locations, evacuation insurance is key. “What company do you use?” my new Canadian friend asks.

For the most part, passenger injuries are limited to the occasional bruise. Peter, the expedition leader, explains the rigors of each foray; even the most difficult hike is less than a mile with little gain in elevation. Staff is always on hand to help passengers over rocks, the way often smoothed by step stools. The biggest danger comes from being so entranced with my surroundings that I forget to watch my feet.

Expedition Day 1: Talbot Bay

If you’ve heard of this place, it’s probably because of the Horizontal Falls. Understanding how they work requires a short lesson in geology. This is where the naturalist/Zodiac drivers come in. Passengers have two options. A one-hour Zodiac cruise takes them past falls’ entrance and back to the ship. I chose the two-hour excursion that also includes a slow ride along a river. This allows plenty of time for Tony, our guide, to talk about the surrounding cliffs.

About 1.8 billion years ago, these rocks sat on a seabed. Over time, tectonic shifts, eruption and erosion created towering layers of sedimentary sandstone bound with silica and the iron ore that gives the rock its fiery red color. Below the tide line, moisture promotes bacteria that create a black band.

Along the way, we see evidence of the region’s huge tidal swing – up to 36 feet here, thanks to the topography above water and below. Even during our short ride, we watch the outgoing tide reveal land that just moments before was flooded.

Bright orange flame fiddler crabs forage on a mudbank beneath mangroves. A big tawny Brahminy kite soars overhead. Our 60-horsepower engines never sit idle, a safety measure in case of crocodiles. And no matter how hot it gets, we are told, dangling a hand or hat in the water is forbidden, lest we lure an aggressive reptile.

The main attraction along this river is the layered rock that twists and folds like a yoga pro. Although some strata stand upright, others twist into toe touches and back bends. Some stand on their heads, turned completely on a vertical edge like pillars. It’s all confounding, especially when you consider the hundreds of millions of minute shifts that have created this landscape.

Cool fact: We’ll find no fossils here. Although scientists debate the timeline for the development of complex cellar creatures, this area is far older than the oldest marine arthropods, which clock in at around 500 million years.

And that takes us back to the Horizontal Falls. Once, the rock faces of the falls might have stood 300 feet or more; today the sides rise 150 feet above the water and nearly as much below. The opening between the two faces is 75 feet wide – forcing water stored behind this narrow gap to roar through at a torrential pace of about 1 million liters per second. Sir David Attenborough has called this one of the world’s greatest natural phenomena. The locals call these roiling rapids “angry waters.”

Tour operators with 300 horsepower fast boats shoot through the gorge before us and a second behind. In our Zodiacs, just bobbing in the fast water is excitement enough.

Expedition Day 2 Morning: Freshwater Cove

A tawny beach stretches across Freshwater Cove. We’re on Worrora lands whose original inhabitants were forced off the land by a variety of ill-informed do-gooders and the greedy – British explorers, missionaries, businesses seeking slave labor.

Some of the traditional custodians are returning, including Gideon, whose ancestors grew up here. They greet us with a short ceremony explaining some of their beliefs and the origin stories of the Wandjina, the mystical beings that shaped this land and its customs. Gideon smudges our cheeks with ochre, a sign that we’ve been welcomed to the land. Now we can explore.

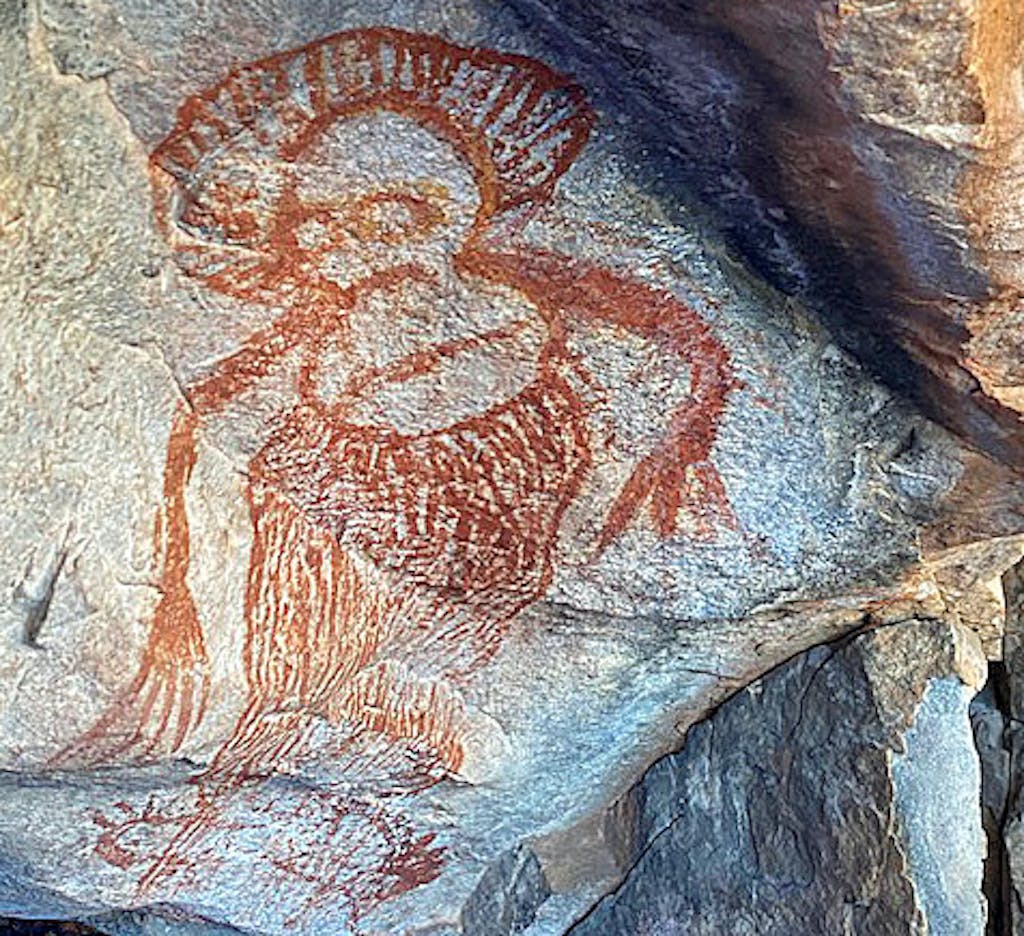

I’m off to see cave art that tells stories from the Wandjina. The path is about a kilometer, a little more than half a mile, winding through a copse of palms, past a 4-foot-tall termite mound and through the tall pandanus grass.

Neil, a cousin of Gideon’s, shows us paintings of a Wandjina, whose headdress is fashioned from feathers that can be cast into the sky to create rain clouds. Two white-faced figures – an owlet and a jarbird – have been refreshed in the last 100 years, indicating that these stories are part of a living culture.

Stories depicted here are parables. (Sharing brings prosperity to all; greed results in bad times.) The drawings are also a paean to the spirits, encouraging them to continue the annual cycle of dry season followed by wet that is critical to bountiful fishing and agriculture.

We pass through a smoky fire – a ritual designed to cleanse our spirits before we return to the Western way of thinking. Gideon warns us away from the water’s edge; Snappy, a 9-foot croc, often patrols the area. Sure enough, from the beach we spot a croc swimming offshore, although it doesn’t seem quite that big. It’s Nibbles, a younger beast, we learn.

Cool fact: Termites build their mud mounds on the centerline of the sun’s path, so they are perpetually climate controlled with heat on the sunny side and coolness on the dark.

Expedition Day 2: Afternoon

At high tide, the southeast edge of nearby Montgomery Reef lies 15 feet beneath the sea’s surface. When it begins to ebb, our Zodiacs motor into the current to watch another rare phenomenon.

Like a rising submarine, Montgomery Reef’s submerged sandstone mass appears, water roaring down clefts and crevasses along the sides in a tidal shift that measures up to 13 feet. The photos we’ve seen at the briefing don’t come close to conveying the mystical feel of this place. Are we in Atlantis? Brigadoon?

The torrent continues; some say as much as an Olympic swimming pool of water is displaced each second. In mere minutes, the tide drops 10 feet or more.

Egrets and heron and beach stone-curlews swoop down to hunt for fish and crabs in the newly formed puddles. Green turtles pop up their heads, periscope-like – often so fast you can scarcely spot them. One Zodiac catches sight of a Stokes’s sea snake. They’re venomous, another reason to keep hands in the boat.

Cool fact: Six of the world’s seven sea turtle species can be found in the Kimberley region.

Expedition Day 3

The entrance to Hunter River feels like a great caldera. The naturalists assure us that there’s been no volcano at play; this is simply a dramatic bay ringed by islands. For passengers with the foresight and funds, this is the staging point for helicopter tours to remote Mitchell Falls, a majestic four-tiered waterfall plummeting more than 250 feet. The (extra cost) excursion is fully booked long before the cruise begins.

Like other parts of northwest Kimberley, the tide here flows in manic swings. Those of us who stay behind explore the vast mangrove system at high tide – for birds and scenery – and low, for crocodiles and mudskippers. Of course, nature has its own ways. The high-tide excursioners are unexpectedly treated to views of a crocodile measuring at least 10 feet. He follows one of the Zodiacs (the driver in charge ensures a respectful distance), and other Zodiacs join for a view. Perversely, the afternoon produces only three faraway views of crocs so small they’re scarcely out of the egg.

There’s a welcome afternoon surprise: dolphins. These are not the standard bottle-nose dolphins found in Florida and elsewhere, but a “snubby” – snub fin – and a “humpy” – a humpback dolphin. Views of the snubby are clear enough for our guide to grab photos she shows at the evening recap.

While the crocs are hiding, mudskippers are frolicking on the exposed beach – or as much as a 7- to-12-inch-long gray sluglike creature can frolic. One flares the sail-like fin on his back and flips into the air, looking to attract a female into his burrow. If he’s successful and they spawn, he gets egg-sitting duty until hatching time (about a week.)

Cool fact: Though they are fish, mudskippers can “walk” on the mud bank on leg-like fins positioned beneath their bodies.

Expedition every day: to the plate

On the sea, Montgomery Reef offers a feast for marine creatures. On board, feasts are delivered by butlers (room service and, on request, afternoon canapes in one’s suite), La Terrazza (the lunch buffet of sushi, salads, roasts and more desserts than ought to be legal) and afternoon tea with fresh scones and finger sandwiches.

I force myself to give up lunch at the pool bar, where the Reuben sandwich is a nearly irresistible temptation on perfectly crisped toast and served with sweet potato fries. For dinner, there’s authentic Italian cuisine in La Terrazza (including penne with walnut sauce) and the evening’s menu in the Restaurant offers choices like barramundi, lobster in a light cream sauce and filet mignon with béarnaise.

For those interested in a splurge, reservations-only La Dame offers a four-course French menu. It comes with a tough decision: Shall we start with caviar with all the trimmings or the escargot? Go on to the lobster bisque or the cream of porcini soup? Glazed duck breast or pan-fried dover sole? For dessert there’s no debate: The pistachio souffle is the obvious choice. The meal is so worth the surcharge that we waitlist for a second visit.

Expedition Day 4: The Rock Art of Swift Bay

The land ringing the wide cove at Swift Bay is less lofty than the soaring cliffs we’ve seen elsewhere. No matter; we’re here to see what’s under the rocks in shallow caves. Here we find more Worrora drawings made with ochre, yellow goethite (an iron mineral) and white pipeclay ground from the rocks. The black is made from charcoal.

These aren’t decorations but more tales of the mystical, powerful Wandjina. Archaeologists think the Worrora and their ancestors have lived here 65,000 years; the rock art dates back only about 4,000 years. But as we learn, these stories date from the beginning of time. When the Earth was still soft, the Wandjina came down from the Milky Way. Their lessons are recalled in the paintings of beings with vast headdresses representing lightning and clouds – a promise to the end of the annual dry season and the rains that will bring food and fertility.

Each has eyes and nose (the source of thunder) but no mouth; if they were to open their mouths, some believe, the land would flood as it did millennia ago after the ice age.

Paintings of fish and crabs, kangaroos and echidna represent the bounty of the wet season. Often, the drawings tell stories of how to live, cook and behave. For clan elders, these were the lessons conveyed to the young in fireside ceremonies.

Cool fact: Over time, the ochre used to make the cave drawings binds with the rock. The local people believe that after the Wandjina finished creating the Earth, they created visual stories of rules and practices, then became one with the rocks. By repainting the most important stories, the local people reinvigorate the power of the Wandjina, aligning past and present.

Expedition Day 6 : Ashmore Reef

Many countries require ships registered in foreign ports to sail in international waters during each itinerary. So it is in Australia. To fulfill that requirement, Silver Cloud sails 200 miles offshore to Ashmore Reef, near Indonesia.

That brings the opportunity for an hour-long Zodiac cruise through turquoise waters to the edge of Ashmore, a marine sanctuary that covers about 365 square miles. An estimated 100,000 birds of 40 species breed here each year.

“It’s like a scene out of Hitchcock’s ‘The Birds,’” says a Zodiac mate, though thankfully, far less threatening. Overhead soar split-tailed frigate birds, pirates that cannot take off from water and instead steal their food from other fishing birds. The white bellies of sea terns take on an aqua glow, a reflection of the sea beneath them. Boobies with red feet and long-tailed jaegers with sly-looking black masks dot the skies and beach.

Too soon, we have to leave. Sailing back to the mainland will take a full night.

Expedition Day 7: Vansittart Bay

Back on the Australian coast, we visit a stretch of land along Vansittart Bay near Western Australia’s northernmost coast. Both of the day’s excursions recall histories that are both more recent and more ancient than what we’ve seen.

Morning brings a beach landing and short walk across a salt pan to visit a World War II memorial in the form of a crashed troop plane. When it ran out of fuel and went down in 1942, the C-53 was evacuating Dutch citizens from Java. All aboard survived.

One engine was later scavenged for parts; the other lies near the metal shell wedged between trees and spinifex grass. Although no one died here, it is a reminder of those who did.

In the moist salt pan, we see elegant fiddler crabs waving their bright reddish claws. Someone spots a few banana fiddler crabs as well, yellow claws in the air.

Cool fact: The male crabs eat with their small claw, using the big colorful claws to wave down and impress females.

Afternoon expedition: Jar Island

In the afternoon we venture to nearby Jar Island, so dubbed by early 19th-century European explorers who found clay jars here. The vessels were like those used by Macassan traders from Sulawesi, Indonesia, who sought sea cucumbers harvested by the local aboriginal people.

Forget the sea cukes. We’re here for rock art sites quite different from those we’ve seen. These lithe dancing figures with tasseled adornments are more artistically sophisticated than the primitive Wandjina drawings, which might suggest they’re more recent. But the reverse is true.

These Jar Island artworks are called Gwion Gwion drawings, after the extinct Gwion birds that once lived here. There’s plenty of speculation about the name, but some scientists say it’s because the birds’ blood was mixed with ochre to create the artworks. Whatever the reason, the paintings inspire respect and awe. Scientists have dated the Gwion Gwion works back 18,000 years, long before Mesopotamians settled the Fertile Crescent and before pharaohs ruled Egypt.

It’s amazing any remain. After the last glacial age, we learned, much of this coast was flooded, likely destroying many works.

Cool fact: The Gwion Gwion paintings – also called Bradshaw art – are likely older than those in the French caves at Lascaux, now closed to the public.

Expedition Day 8: Koolama Bay

The King George River cuts inland through a wide gorge. Red rock walls rising 250 feet seem friable and frail, wedged precariously atop pillars carved by time and tide. It seems they might fall any time, although they’re sturdier than they look, we’re told.

Mangroves line the shore, providing shelter for young (and today invisible) crocodiles and the small fish that sometimes flit above the surface. A peregrine falcon soars on the thermal currents overhead. A white-necked heron perches high atop a sandstone tower, carefully watching our Zodiacs from afar. We catch a fleeting glance of a rock wallaby leaping from one shady ledge to the next.

In the morning light, the rocks seem to glow. We motor down the seven miles of the river, past plants growing in damp crevasses and stone honeycombed by salt crystals that expanded with the elements.

We hear the falls before we see them, a mere rivulet compared with the torrential gush of the wet season. But even in its diminished state, the water is formidable as it cascades 250 feet from ledge to water. At this time of year, there are two falls, separated by thick partitions of sandstone. One is easier to navigate than the other, and our Zodiac driver gives in to our cries to cool us off with a splash under nature’s spigot.

Expedition Day 9

The final expedition day brings us to the historic town of Wyndham, home to 900 hearty souls who work at the small commercial port and regional cattle operations. We’ve been offered three forays into the surrounding outback: a cruise onto the Ord River to look for birds and rock wallabies, sightseeing flights over the ancient sandstone “beehives” that make up the Bungle Bungles, and a day-long visit to El Questro, 700,000 acres of rugged wilderness traversed by five rivers.

The other solos and I are split between El Questro and the Bungle Bungles. A cold has hit our ranks, and only two make it off the ship and onto El Questro excursion. My Canadian friend reports the views magnificent and worth a lengthy bus ride. I’ve stayed in bed, knowing that when my body says “quit.” I need to listen.

Day 10

We sail toward Darwin, home to the excellent Darwin Military Museum (don’t miss the audio stories from evacuated families) and launch point for the vast Kakadu National Park.

Too soon, we’re there.

Addresses have been traded with friends I’ve made along the way. The cold-stricken solos have emerged from their suites and been whisked to the airport. I have time for a stroll along Darwin’s cozy shopping street before my flight.

But for me, at least, the trip isn’t over. Weeks later, I’m still pondering the Gwion Gwion drawings and the stories of the Wandjina. I close my eyes and see towering red rocks and glowing sunsets. Like the rock wallaby, I’ve made my own leap into the unknown and landed on ground that feels stronger than when I left home.