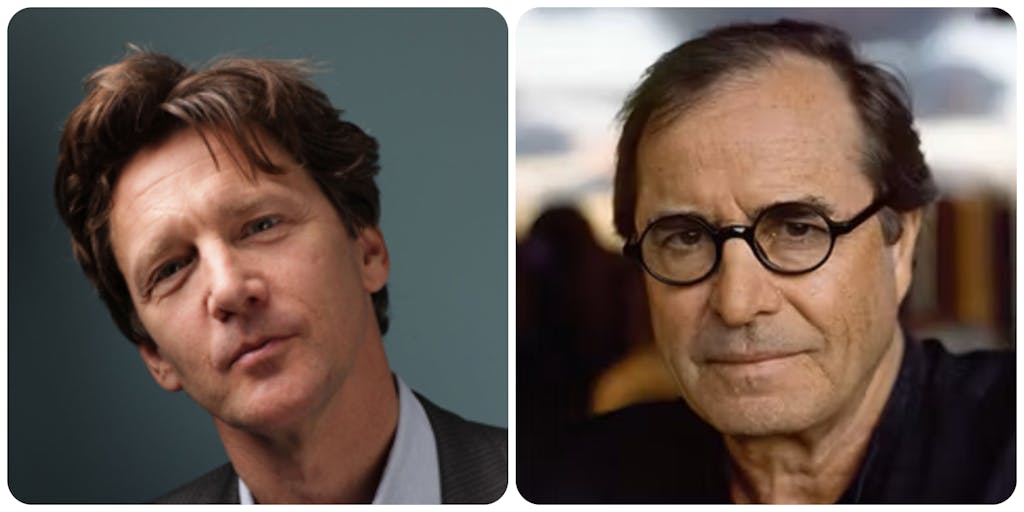

Andrew McCarthy is in conversation with … Paul Theroux

In 1975, novelist Paul Theroux set off on a train journey through Asia to write what would become a seminal work, “The Great Railway Bazaar.” Displaying Theroux’s trademark candor, professionalism and curiosity, the book redefined what a travel narrative could be and influenced a generation of travel writers, myself included, who would come in his wake .

I first interviewed Paul a decade ago for his swan song to Africa, “The Last Train to Zona Verde.” We caught up this time just before his cruise to Norway with Silversea. I found Theroux, now 82 and hard at work, as always, full of passion and verve. Here is our conversation.

Andrew McCarthy: You’ve been doing a fair bit of cruising lately. What do you like about it? And for someone who values his freedom as much as you appear to value yours, do you ever feel trapped onboard?

Paul Theroux: I felt trapped when I sailed on ships, having little money, going third class, such as crossing the Atlantic on the Queen Frederica (sent to a breaker’s yard [scrap yard] in 1977). I was in a lower-deck cabin with seven migrants to Canada from Lebanon and Sicily. Nice guys! But no privacy.

On a luxury cruise I can write in the splendor of my cabin. Or in nice weather on a secluded part of the ship. Great meals. The occasional excursion. Heaven.

AM: I recently read, and loved, Joseph Conrad’s “Typhoon,” a seemingly simple tale of a ship surviving a storm. What are some of your favorite nautical/ maritime books?

PT: I love Conrad and even wrote an introduction to “Typhoon” for the Folio Society [creators of lushly illustrated books]. I would include Twain’s “The Innocents Abroad,” for which I also wrote an intro – the ultimate cruise ship narrative! I have read many maritime adventures that recount ordeals. Two come to mind: “Survive the Savage Sea,” by Dougal Robertson. A true story. And the novel “Boon Island,” by Kenneth Roberts. Fridtjof Nansen’s “Farthest North” [is] also a great sea story.

I think Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s “The Worst Journey in the World” is a masterpiece. I have always preferred books about difficult journeys.

Paul Theroux

AM: Long ago, I was given a copy of “The Old Patagonian Express,” your book about your train journey through South America. It opened my eyes with the idea to go, go far, go alone, get out of touch and don’t come back for a long time. That coupled with the curiosity you display and your clear-eyed observations, it all added up to my viewing the world differently – that book changed my life. What books changed yours? Any travel books?

PT: The books I mentioned above. Also, the books I read as an impressionable youth, by Richard Halliburton. I think Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s “The Worst Journey in the World” is a masterpiece. I have always preferred books about difficult journeys. Another is “The Fearful Void,” by Geoffrey Moorhouse, his crossing of the Sahara.

AM: How do you approach writing differently now than you did when you were, say, back in Africa in the Peace Corps?

PT: I haven’t changed much. I write a first draft in longhand. I sometimes recopy this in longhand (ballpoint pen, lined white paper). Then I type the whole thing. A laborious process. But it works for me.

AM: The same question regarding travel: How has the way you travel evolved over the years? Are you a planner or do you just go?

PT: I do a little more planning these days. I used to simply set off. In my last two books – “ Deep South” and “Mexico” – I rediscovered the freedom of a solitary road trip in my car.

AM: In reading you for so long and in so many different moods, fiction, travel, memoir, the common chord, it seems to me, the thing that drives you, that propels not only your narratives but you personally, is your need to see things clearly, to see what is. True?

PT: Yes, curiosity to see the truth of the human aspects of a place, figures in a landscape. Listening to people’s stories. Testing my powers of observation. Also, the bliss of being alone en route. And in my long life, seeing how the world has changed.

AM: You’ve spoken in the past about “escaping” your home in Massachusetts when you were young. You’ve traveled the world, yet you always return to Massachusetts, to the Cape, so the question is, can we ever escape? And was Thomas Wolfe wrong? Can we ever not go home again?

PT: I needed to escape the scrutiny of my family. And I fantasized about exotic places from an early age. But I must add that I loved the long, hot summers by the sea in New England when I was growing up. I return to them every year, to swim and be with my wife and write and grow tomatoes.

AM: Tease me about your next book, “Burma Sahib” [due out February 2024]. And why [George] Orwell?

PT: My book is a novel.

When Eric Blair – Orwell’s real name – left Eton, he decided not to go to Oxford with his friends. He joined the Indian Imperial Police and became a policeman in Burma. He was 19. Amazing. Though he hated the work, he followed orders for five years. It was the making of him as a left-wing anti-colonial. Very little is known of his life at that time. He wrote a novel “Burmese Days” and some essays.

Oh, yes, he was inspired by Rudyard Kipling who said, “We have only one virginity to lose, and we never forget where we lost it.” Blair lost it in Burma and turned into George Orwell.

AM: You’re obviously quite prolific, so complete this sentence. “If I didn’t write I’d…”

PT: If I didn’t write I’d be a very frustrated person.