A Slice of the History of South America via 18th-Century Depictions of the Amazon

Produced in collaboration with Silversea’s partner, the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), “Relics of History'”delves deep into the annals of exploration. It showcases the most fascinating artifacts from the Society’s expansive and unique collection, which comprises approximately two million items, tracing 500 years of geographical discovery and research.

In a presentation that helps us understand the history of South America, principal librarian of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG), Eugene Rae, explores the achievements of two iconic European explorers, Percy Harrison Fawcett and Professor John Walter Gregory. Artist Victor Coverley-Price also accompanied the latter, who undertook pioneering explorations of South America. Both Fawcett and Gregory pushed the bounds of geographical understanding, charting territories that were unknown to the European community.

Hand-sketched maps by Major Percy Harrison Fawcett

Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett was a British archaeologist and explorer who, along with his son, disappeared under unknown circumstances in 1925 during an expedition to find what he believed to be an ancient lost city in the uncharted jungles of Brazil.

Fawcett was born in 1867 in Devon, England. In 1886, he received a commission in the Royal Artillery and served in Trincomalee, Sri Lanka, where he also met his wife. Later, he worked for the British Secret Service in North Africa and learned the surveyor’s craft. He was also a friend of authors H. Rider Haggard, and Arthur Conan Doyle, who used Fawcett’s stories as an inspiration for his “Lost World.”

Fawcett’s first expedition to South America was in 1906 when he traveled to Brazil to map a jungle area at the border of Brazil and Bolivia at the behest of the Royal Geographic Society. The Society had been commissioned to map the area as a third party, unbiased by local national interests. He arrived in La Paz, Bolivia, in June.

Fawcett made seven expeditions between 1906 and 1924. He mostly got along with the locals, bearing gifts, patience and courteous behavior. In 1910, Fawcett made a trip to Heath River to find its source. He returned to Britain to serve in the army during World War I, but returned to Brazil after the war to study local wildlife and archaeology.

In 1925, Fawcett took his older son Jack with him to look for a lost city he had named “Z.” Fawcett had studied ancient legends and historical records and became convinced that there was a lost city somewhere in the Matto Grosso region. He left a note stating that if they did not return, no one should send a rescue expedition to try to find them; they might suffer their fate.

The last communication from Fawcett was on May 29, 1925, when he telegraphed his wife stating that he was ready to venture into unexplored territory with Jack, and Jack’s friend, Raleigh Rimmell. They were last reported to be crossing the Upper Xingu, a south-eastern tributary of the Amazon.

There were a number of supposed sightings of Fawcett in the following years, as well as many expeditions sent to discover what had become of the lost team, including one led by G.M. Dyott in 1928. The Dyott expedition failed to uncover any conclusive evidence, and none of the apparent sightings could be substantiated. Fawcett was officially declared dead in 1937, but the mystery of his disappearance remains. It is now part of the fabric of the history of South America we may never know.

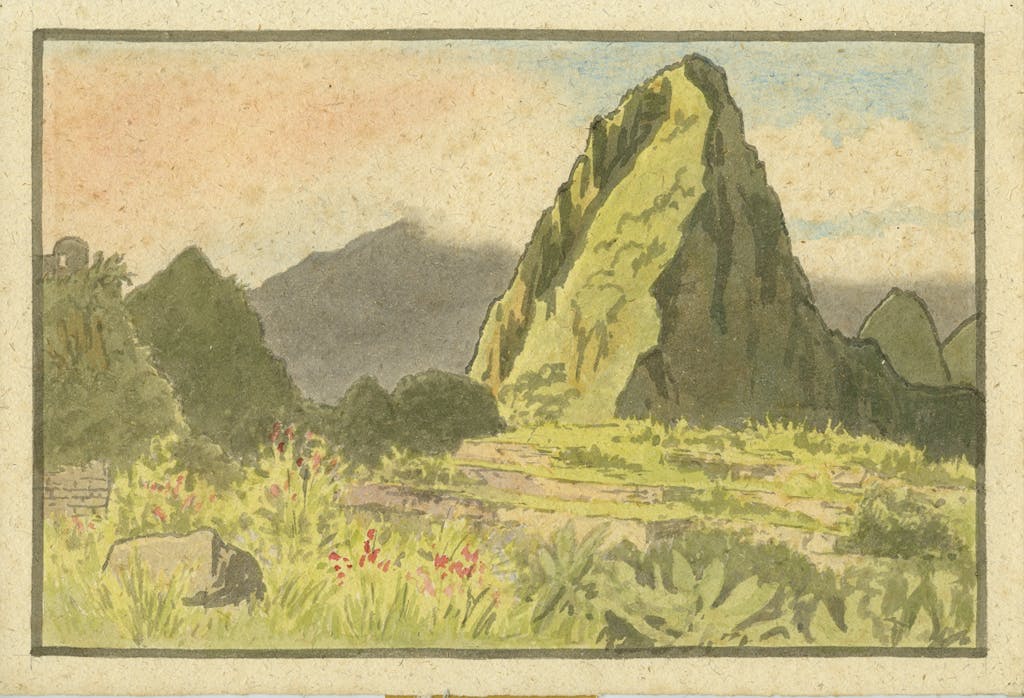

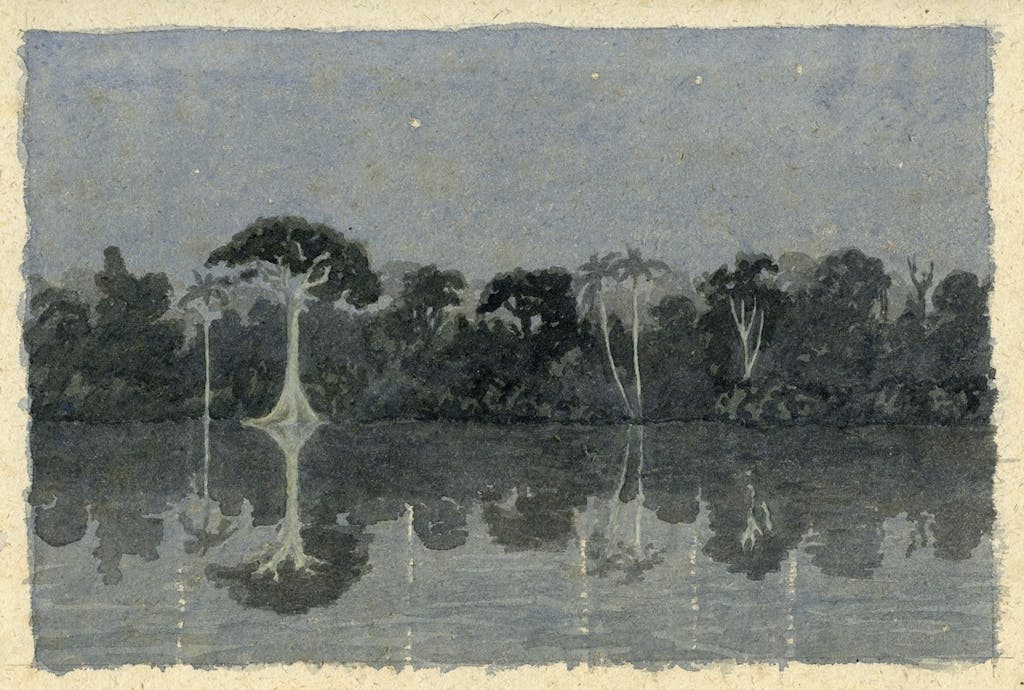

Watercolors by Victor Coverley-Price

Born in 1901, Victor Coverley-Price was largely a self-taught artist. He studied modern languages at university, during which time he continued to paint, choosing wherever possible to capture in sketches and watercolors the people and places he encountered on his travels through Europe.

He chose a career in the British Foreign Office, which fitted his abilities with foreign languages and also offered him the opportunity to travel more widely. From 1925-45, he traveled to a diverse range of postings; from Nepal to Japan and from South America to the Middle East. His paint box never far from his side, Coverley-Price had soon developed a unique artistic style, which captured landscapes around the world.

In 1932, he was invited by the Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society to join Professor J.W. Gregory as an interpreter on his forthcoming expedition to Peru. The expedition’s aim was chiefly concerned with the geological exploration of three distinct areas: the coastal cordillera of Peru, the central section of the Peruvian Andes and the eastern face of the Andes into the Amazon basin.

During the expedition, Coverley-Price found time to document the beauty of the landscape as they traveled, often in great peril, along the river systems: “Sometimes we were swept from side to side in confused water; sometimes we were heading directly for a boulder where the water rose in a seething mass of foam, like a saucepan of milk that is about to boil over.”

Professor Gregory met his death toward the end of the expedition when he was swept downriver after his canoe capsized on the powerful Pongo de Mainiquiri rapids of the Urubamba River in Peru. Luckily, Coverley-Price, his paintings and the majority of scientific material from the expedition survived the accident. After the disaster, Coverley-Price traveled for a further 11 days downriver to the telegraph station in Masisea, on the Ucayali, where he reported the incident back to England.

Intrigued by the story of the Lost City of Z and South American history? Read more here.

About Silversea’s collaboration with the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG)

Since 2013, Silversea and the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) have joined forces to spread knowledge collated from centuries of scientific exploration. Through this partnership the Society has enriched Silversea guests’ expeditions with over 500 years of travel and discovery. Founded in 1830, the Royal Geographical Society is a world center for geography: supporting research, education, expeditions and travel.