Salmon Run: When to Go Salmon Fishing in Alaska

It’s a cool summer morning at Geographic Harbor in Alaska, and I’m sitting on a Zodiac watching a female brown bear gently nudge her two cubs towards a flowing stream. After an initial prod in the right direction, she walks steadily towards the water and occasionally turns around, as mothers do, to check they are still following. It’s currently the salmon fishing season in Alaska, and there’s no doubt she has her family’s next feed on her mind.

Of course, the cubs are too busy playing to notice — they paw and pat each other as they roll about in the foliage before catching up to their mother. They are around two and a half years old and still learning to navigate the world away from their den.

Once at the stream, the sow paces up and down along the pebble surroundings while working out the best place to cross. Then, after establishing her chosen spot, she takes to the water with a splash and stops abruptly right in the middle of the flow, her nose pointing down as she uses her paw to make her catch. As her head lifts, I see she has achieved her mission. This bear has caught a salmon.

She crosses to the other side of the stream with the fish firmly between her teeth, and I note this particular salmon’s story — despite its unpleasant demise — is not about to end here. In fact, while salmon are widely recognized as a significant part of this Alaskan ecosystem, its integral position within this thriving environment’s circle of life is more far-reaching than I realize.

“That is the beauty of a functioning ecosystem,” explains fisheries expert and Silversea expedition expert Luke Kenny. “Everything relies on everything else to a degree, either directly or indirectly. Everything relies on salmon.”

When do salmon run in Alaska?

The salmon run typically starts in the springtime, around April or May, and runs into the autumn depending on the geographic area and species. The run isn’t consistent from year to year both in terms of numbers of fish and timing, and the main runs take place in July and August.

“King salmon are usually the first to return. For that reason, they are sometimes referred to as ‘spring salmon,'” Kenny says. They are followed by the other four types of salmon in Alaska: sockeye, pink, chum and silver.

While the species do overlap in their geographic ranges, pink salmon are known to spawn closest to the ocean, in the lower reaches of rivers and streams. King, sockeye, silver and chum salmon habitats tend to thrive further up the big rivers and in some short to medium length rivers, too.

“Salmon bury their eggs in permeable gravel,” explains Kenny. “This allows clean and oxygenated cold water to reach those eggs. Unfortunately, activities such as logging operations cause soil erosion, which often blocks the gravel.”

The salmon’s life cycle

Brown bears consume what is seasonally available to them, including berries, grass, insects and fish. Salmon, however, become most vital to their diet in the autumn, when they need to put on massive amounts of weight in preparation for winter hibernation. Then they concentrate on eating the fatty parts of the fish, particularly the layer of fat under the skin and the oil-rich eggs.

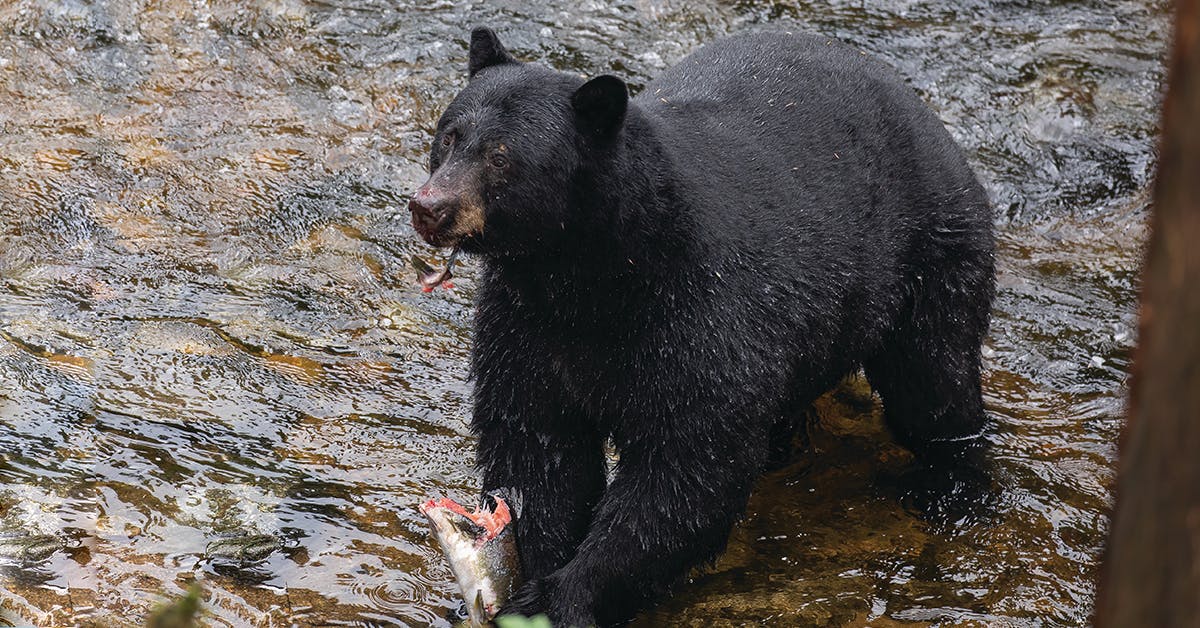

It’s not just brown bears who benefit from a flourishing salmon run in Alaska. Many species, such as orcas, seals, black bears, wolves, eagles, gulls and ravens, do, too. “Or anything else that scavenges the salmon carcasses as they float down river or get abandoned in the forest by over-fed bears,” adds Kenny.

Piles of salmon carcasses eventually lodge in pools and bends and slowly break down. “The decomposed salmon in the forest — along with the feces of bears, wolves and birds — adds nitrogen, phosphorus, sulfur and carbon to the forest. It provides food for a whole host of other creatures, building a habitat for large predators,” he explains. “Meanwhile, anything left in the river helps to enrich that freshwater ecosystem, feeding various invertebrates and the nymphs of insects.” Eventually, this injection of fresh nutrients will feed and nourish the new, young salmon to come.

The impact of salmon fishing in Alaska

While stocks of salmon in the Pacific Northwest were heavily overfished in the early 20th century, the fishery is now reportedly managed more successfully despite demand remaining high. This is mostly due to the practice of hatchery release supplementing the wild salmon populations.

Kenny explains, “Here, mature fish in a river catchment are collected before spawning, allowing the eggs and milt [sperm] to be stripped from the fish.” Next, the eggs are fertilized and reared in a controlled hatchery environment. “These larvae are then released into the river system, allowing them to have that river’s characteristics imprinted on them, and so they should grow and develop as normal wild fish would.”

Successful development leads to these salmon returning to the same river, increasing the population available to be fished. So far, the system has worked, with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game confirming the commercial fleet caught 39 million hatchery-produced salmon in 2018.

Only a small proportion of the natural wild stock are selected to increase chances of survival, which could have implications for the future. “That small selection doesn’t necessarily have the most suitable genes to overcome future challenges brought on by changing environmental conditions,” explains Kenny. “We have tampered with the natural genetic makeup that took millions of years to develop, and offered variability to overcome new pressures. So now, we must supplement the population with hatchery releases as it cannot survive unaided.”

The future isn’t so bleak, though, as there are some solutions. “While Alaskan salmon is only one small part of this global issue, we need to realize that conditions are changing for these fish,” concludes Kenny.

As the female bear and her two cubs head off into the woodland behind the stream, I find myself sincerely hoping they will continue to thrive in this beautiful environment. I think of what might happen to this little family come autumn. Will they find enough salmon to feed on? Will they survive through their winter hibernation?

Although I’ll never know how they fared, I come away from my Alaskan cruise experience cherishing the remarkable memory of those bears salmon fishing in Alaska. But now I have the humbling understanding that, in Alaska, wildlife scenes like these are just one small part of the interconnected nature of the ecosystem.

Would you like to learn more about salmon fishing and Alaska? Read more here.