Myanmar’s ‘Races Village’ Invites You to Learn More About the Nation’s Diversity

Inside a wooden stilt home in Yangon, Myanmar, two black eyes stare at me through the dim light. I spot them amid this gloom only because of the contrast provided by the gilded head in which they sit. This gaze belongs to a Zee Kwet owl, which for centuries in Myanmar has been handcrafted in papier mâché and daubed with shimmering paint. It is a glowing centerpiece in this sparsely decorated living room, illuminated only by two small windows in a dark, teakwood interior.

I’m standing in a replica of traditional homes found in many Myanmar towns. Zee Kwet are not mere ornaments in such abodes. Instead, their role is to attract fortune and repel evil.

They are amulets for the Bamar people, one of eight ethnic groups from Myanmar whose cultures are showcased here in the National Races Village, a 150-acre open-air museum in the country’s biggest city. While wandering this forested tourist attraction, I observed the architecture and artforms of the Bamar, Kachin, Karen, Kayah, Mon, Rakhine, Chin and Shan groups.

Although people from Myanmar usually are called Burmese, the population of 54 million is contains more than 130 ethnic groups. Many of these communities, spread across this vast country, are difficult for tourists to visit. In 2002, the government built the National Races Village, which it claimed would let tourists “feel and experience every state of Myanmar.”

That was a lofty aim, given Myanmar’s diversity: 130 ethnic groups in a country that also has five main religions – Buddhism, Islam, Hinduism, Christianity and animism – according to the Minority Rights Group International, a non-governmental organization, or NGO.

“Burma’s geographic position has resulted in the country attracting settlers from many different backgrounds throughout its long history,” MRGI’s website says. “Minority ethnic communities are estimated to make up at least one-third of the country’s total population and to inhabit half the land area.”

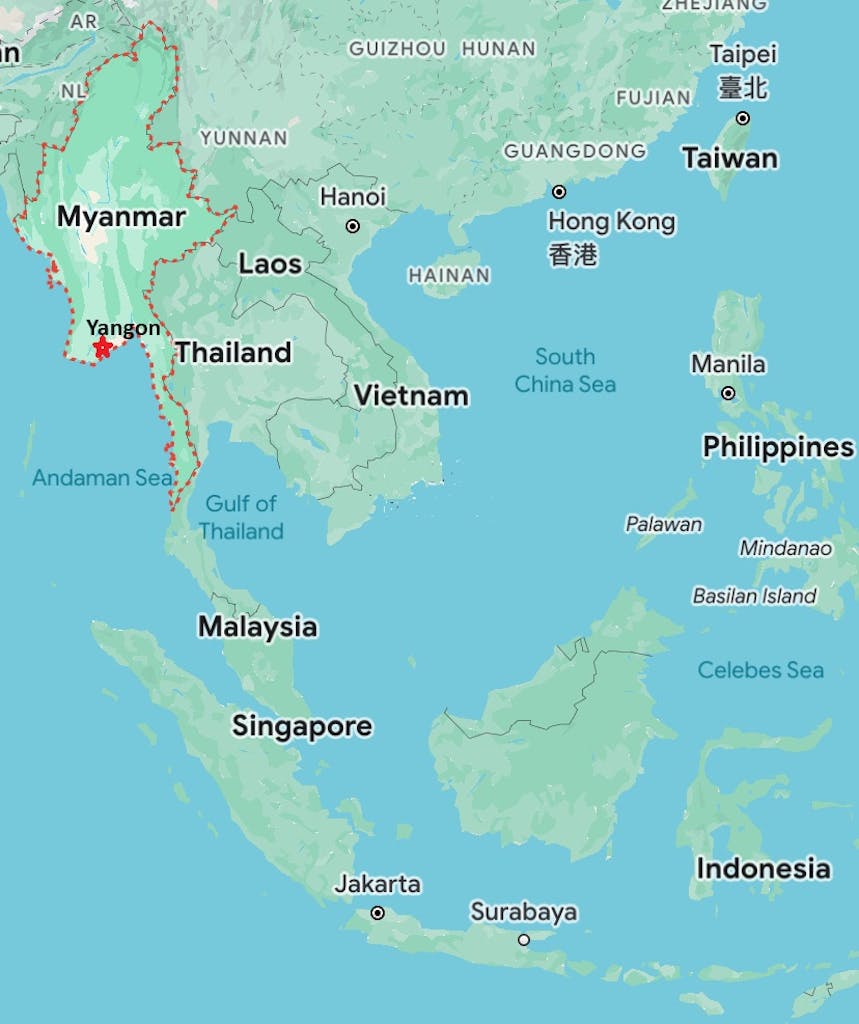

The gateway to Myanmar

Myanmar’s size and location help explain this. It is larger than any European country and is only slightly smaller than Texas. Myanmar is part of Southeast Asia, bordered by Thailand and Laos to its east, yet its western edge hugs the Indian subcontinent and directly to its north looms China.

I saw, smelled and felt these disparate influences across several visits to Yangon. Buddhist monks knelt alongside me inside Sule Pagoda. Fire-spewing dragons towered overhead, decorating pillars at Chinatown’s Kheng Hock Taoist temple. Incense smoke from Shri Kali Hindu temple drifted past me and off into the bedlam of Little India.

Yangon, a city of almost 6 million people, is the gateway to Myanmar. Pre-pandemic, tourism was mushrooming, increasing from 762,000 visitors a year in 2009 to 4.3 million in 2019. Most visitors fly in and out of Yangon, and few venture beyond this booming metropolis, where highways, condominiums and shopping centers sprout like flowers. Those visitors who do leave the capital usually head only to Bagan, a photogenic city embellished by 2,000 ancient temples and pagodas.

As a result, foreigners miss many of Myanmar’s wonders, such as the magnificent Mrauk-U. Spread across an area almost as large as Manhattan, 200 Buddhist stupas, temples and monasteries remain from what 500 years ago was the grand capital of the Arakanese Kingdom.

To reach Mrauk-U from my home city of Perth, Australia, I took three flights, followed by a three-hour road trip through Rakhine State. That’s how I was able to experience some Rakhine culture at Yangon’s National Races Village.

It takes a village

The entrance to its Rakhine area is marked by a scaled-down version of a Mrauk-U masterpiece. Htukkanthein Temple, designed to thwart military attacks and venerate Lord Buddha, is distinctive. You reach this grand, bell-shaped tower, perched on an elevated platform, by taking multiple staircases.

This village does not mention the Rohingya, a Muslim minority mostly from Rakhine State that the Myanmar military has persecuted. Instead, the focus is on Rakhine artforms, such as its delicate earthenware, conical hats woven from bamboo and its narrow, 30-foot-long racing boats.

The latter are hand-crafted from jackfruit wood and oar-powered during annual events that date to the Arakan Kingdom era. Carved into the stern of the racing vessel is a commanding bird. I admired its red-and-white plumage and pondered the reptilian scales on its neck. A staff member tells me this is a Galon, or Garuda, a legendary creature from Buddhist and Hindu mythology.

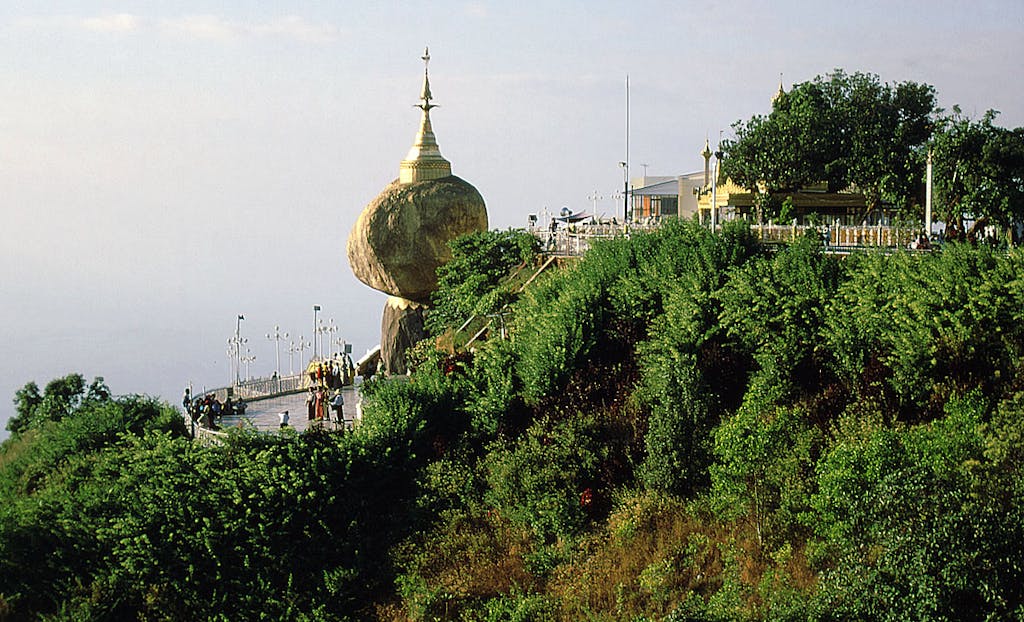

Buddhist landmarks from across Myanmar are featured throughout the National Races Village. These scaled-down replicas include the golden Kyaiktiyo Pagoda, a historic site of pilgrimage for one of the highlighted ethnic groups, the Mon.

Nearby is a re-creation of Taung Gwe Pagoda, a hilltop temple more than 700 years old and is sacred to the Kyah people.

Even more miniaturized, understandably, is Mount Hkakabo. Myanmar’s tallest peak. Nearly touching heaven at more than 19,000 feet , it’s the tallest mountain in Southeast Asia and a blessed location to the Kachin people.

The original versions of all these landmarks are well removed from Myanmar’s tourist trail. Kyaikhtiyo is the closest to Yangon but still a nine-hour round trip by road from that city.

More memorable than these landmarks: the inspiring creativity, engrossing symbolism and dense history embedded in each of the eight traditional homes. An assortment of intricately decorated Burmese marionettes, each representing Imperial characters hang from the teak façade of the Bamar house.

They star in Yokthe Pwe, a 500-year-old form of puppet theater that also features the Nats, a group of spirits worshipped in animistic Burmese folk religions. Across Myanmar, these supernatural beings are honored with gifts of food or flowers.

I saw blossom offerings throughout the complex, although absent signage, buy I couldn’t be certain of their meaning. Such intrigue is common when traveling in Myanmar. Few nations rival its deep trove of rituals, dialects, artforms and peoples.

The National Races Village examines only eight of its more than 100 ethnic groups. Yet I departed with the sense I’d just traversed continents, having learned about sublime artforms, admired distinctive architecture and having met Imperial figurehead and looked into the eyes of an inanimate owl animated by mythology.