Postcards from a New World: 19th Century Paintings of South America

The 19th century was an era rich in exploration and discovery as Europeans began to delve deeper into the mysteries of the New World. In addition to scientific expeditions that mapped, measured, and monitored the South American continent, artists also flocked there to capture its dazzling landscapes and exotic flora and fauna for the first time. And audiences were enthralled by the vision of South America that they depicted.

Three artist-explorers led the way in this seminal portrayal of the lands and peoples of this previously unfamiliar region to outsiders: the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, the American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, and the German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas.

Alexander von Humboldt

Nobody did more to put South America on the map than the influential scientist and explorer Alexander von Humboldt, an intellectual superstar of the 19th century. During his unprecedented five-year tour of South America, Mexico, and Cuba between 1799 and 1804, he not only corrected the location of many cities there, crucially updating the cartography of the region, but he also collected, studied, and sketched the new plant specimens and artifacts he encountered and depicted the people and landscapes as well.

When he first arrived at Cumaná, Venezuela, in 1799, he could not contain his astonishment and wrote to his brother Wilhelm: “What color of birds, fish, even crabs (sky blue and yellow)! So far we have wandered like fools; in the first three days we couldn’t identify anything, because one object is tossed aside to pursue another. Bonpland [his traveling companion] assures me he will go mad if the marvels do not stop. Still, more beautiful even than these individual miracles is the overall impression made by this powerful, lush and yet so gentle, exhilarating, mild vegetation.”

He was so inspired by the exuberance and grandeur of the natural world in South America that he came to see the wonders of nature as powerful aesthetic and cultural attributes, every bit as important as the architectural treasures of the Old World. “Nature herself is sublimely eloquent,” he wrote.

On his journey through today’s Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, and Mexico, Humboldt didn’t take a draftsman along. Instead, he sketched his impressions himself. Guided by his sharp eye and scientific discipline, he executed his line drawings quickly and precisely. During his trip, he produced 450 illustrations of plants, animals, and landscapes that brought the continent visually to life. His paintings of soaring Andean mountains and smoldering Ecuadorian volcanoes were among the first views of the Americas ever seen by European eyes. And his detailed observations of Latin American flora and fauna as well as of indigenous people are not only scientifically and historically accurate, but also beautiful works of art.

He also forged new paths. He explored the Upper Orinoco River in a large canoe, a 75-day, 1,400-mile journey through wild and mostly uninhabited territory full of exotic animals and plants that would become subjects for his work. And he climbed Ecuador’s 20,500-foot-tall Mt. Chimborazo in 1802, considered the world’s highest mountain at the time. No one had ever made it to the top and though he fell short, he and his crew climbed higher than anyone else in recorded history. His record held for 30 years.

His groundbreaking discoveries during these journeys became the source of much of our current knowledge of tropical zoology, botany, geography, and geology. Almost 300 plants and more than 100 animals are named after this trailblazer — considered the father of modern geography — as is the famous Humboldt Current that parallels the Peruvian coast.

His expedition reports, Views of the Cordilleras and Monuments of the Indigenous Peoples of the Americas and Voyage to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent, published in the early 1800s, contain brilliantly engraved drawings and detailed texts about the wildlife, cultures, and landscapes of the Americas. They transformed how Europeans perceived the New World and inspired others to follow in his footsteps.

Frederic Edwin Church

One such acolyte was the celebrated American landscape painter Frederic Edwin Church, a seminal figure of the 19th-century Hudson River School art movement. Using Humboldt’s Views of the Cordilleras as a guidebook, Church retraced some of Humboldt’s voyage on his first trip to South America, a seven-month journey to Colombia and Ecuador in 1853.

In Colombia, he ascended the Magdalena River by canoe and traveled overland by mule, which inspired him to refer to the “green and exuberant vegetation” in his journal and to create several versions of his pastoral View on the Magdalena River. Just like Humboldt, Church was gobsmacked by the scenery he encountered. Once in Ecuador, he described it as “a view of such unparalleled magnificence … that I must pronounce it one of the great wonders of Nature … My ideal of the Cordilleras is realized.” He was especially taken with snowy Mt. Chimborazo, which he later incorporated into several paintings.

During the trip he produced drawings and oil sketches of the mountains and flora he encountered with the accuracy of a true naturalist, echoing Humboldt. He later incorporated these into the large-scale compositions that he painted back in his studio.

He turned out one such work, South American Landscape, in his New York studio two years after returning from Ecuador. It is a fanciful composite of motifs from his drawings and oil sketches, such as a lone palm tree (his favorite tropical trope), a hillside church, a waterfall, and the great Chimborazo volcano. Bristling with the remarkably rendered details for which Church was rightly famous, it realistically depicts the dense, lush vegetation, snow-topped Andean peaks, and charming colonial churches.

For his multiple versions of View of Cotopaxi, Church used Humboldt’s engraving of Ecuador’s active volcano as inspiration. And for In the Tropics and Tropical Landscape, he captured the exuberance of South America’s exotic vegetation. These and other paintings that resulted from his first trip captivated the U.S. public with their convincing realism, at a time when interest in South America had already been powerfully aroused by Humboldt. Church’s skillful combination of the precision required by geology and botany with the aesthetics of landscape art produced works of dazzling technical mastery and enormous beauty.

On a second trip to South America in 1857, Church studied Mt. Chimborazo, known as “Humboldt’s Mountain” after the great German naturalist had climbed it in 1802. Church paid homage to this feat with works like Mount Chimborazo, Ecuador. This trip also inspired his masterpiece, the panoramic Heart of the Andes, which was painted as a tribute to Humboldt. Its startling realism — it depicts more than a hundred identifiable plant species, including the passion flower and the morning glory vine originally catalogued by Humboldt — invites the viewer to step right into the scene and become part of an Edenic paradise. Church enhanced the realism by using tropical plants brought from his trip when he unveiled the enormous painting to an astonished public in New York City in 1859. After being charged admission, viewers were even provided with opera glasses to better examine the painting’s details. Heart of the Andes (today in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art) was a runaway success and eventually sold for $10,000, the highest price ever paid for a work by a living American artist at the time.

Johann Moritz Rugendas

Among the many 19th-century artists inspired by Humboldt, Johann Mortiz Rugendas is considered by scholars “by far the most varied and important of the European artists to visit Latin America.” At only 19 years old, he first traveled to Brazil in 1821 as an illustrator on a scientific expedition. There, he produced sketches, studies, and watercolors of the landscapes, flora and fauna, villages, and peoples of the coastal towns from the Province of Rio in the south to the Province of Pernambuco in the north. He also documented daily life in Rio de Janeiro at a time when Brazil was struggling for independence. Back in Europe, he published his monumental book Picturesque Voyage to Brazil in 1835, which contains more than 500 illustrations. It was considered one of the most important documents about Brazil in the 19th century.

During his trip home, he met Humboldt in Paris, who was impressed by his illustrations. Encouraged by the great polymath himself, from 1834-1846 Rugendas traveled to Mexico, Chile, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Uruguay and returned to Brazil. Welcomed by the court of Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil, he even created portraits of several members of the royal court. His expressed goal for this trip was nothing less than “an endeavor to truly become the illustrator of life in the New World.” In this, he largely succeeded. His work became a unique pictorial representation of South America in the mid 1800s.

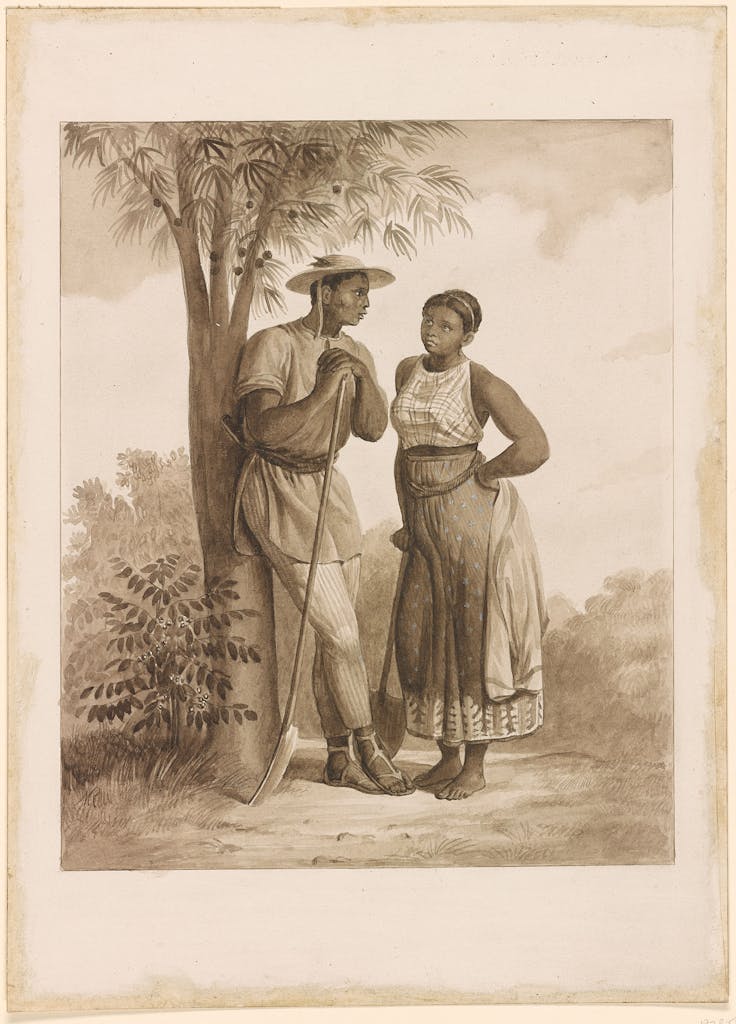

Whereas Humboldt and Church focused more on South America’s natural landscape, Rugendas was obsessed with documenting its peoples and cultures. Embracing a kind of tropical romanticism popular at the time, he repeatedly illustrated black people, showcasing their physical characteristics and personal adornments to demonstrate their varied origins. When painting scenes of commercial activities, however — such as street commerce, transportation, or laundry — he depicted a more generic type of Black. While he didn’t shy away from difficult subjects, such as the lithograph, Slave Market, he often rendered the Blacks he saw with deep tenderness and respect, such as the pen and ink, Man and Woman with Farm Tools on a Brazilian Plantation. Like the abolitionist Humboldt, Rugendas disapproved of Brazil’s slavery system and supported gradual emancipation and racial harmony.

He also depicted indigenous, mestizo, and European cultures with revealing accuracy. The Huaso and the Washerwoman shows a bucolic scene of the encounter of a Chilean huaso, or cowboy, with a laundress along an idealized burbling stream. Meanwhile, his canvasses, View of Lima and The Church of Andacollo (in Chile), lovingly portray the varied members of society — from traditionally clad native people to rough-hewn farmers to dandified wealthy gentlemen. His colorful Fiesta of San Juan Amancaes is a riotous depiction of this feast day in Lima, Peru, in which all social strata mingle with joyous abandon.